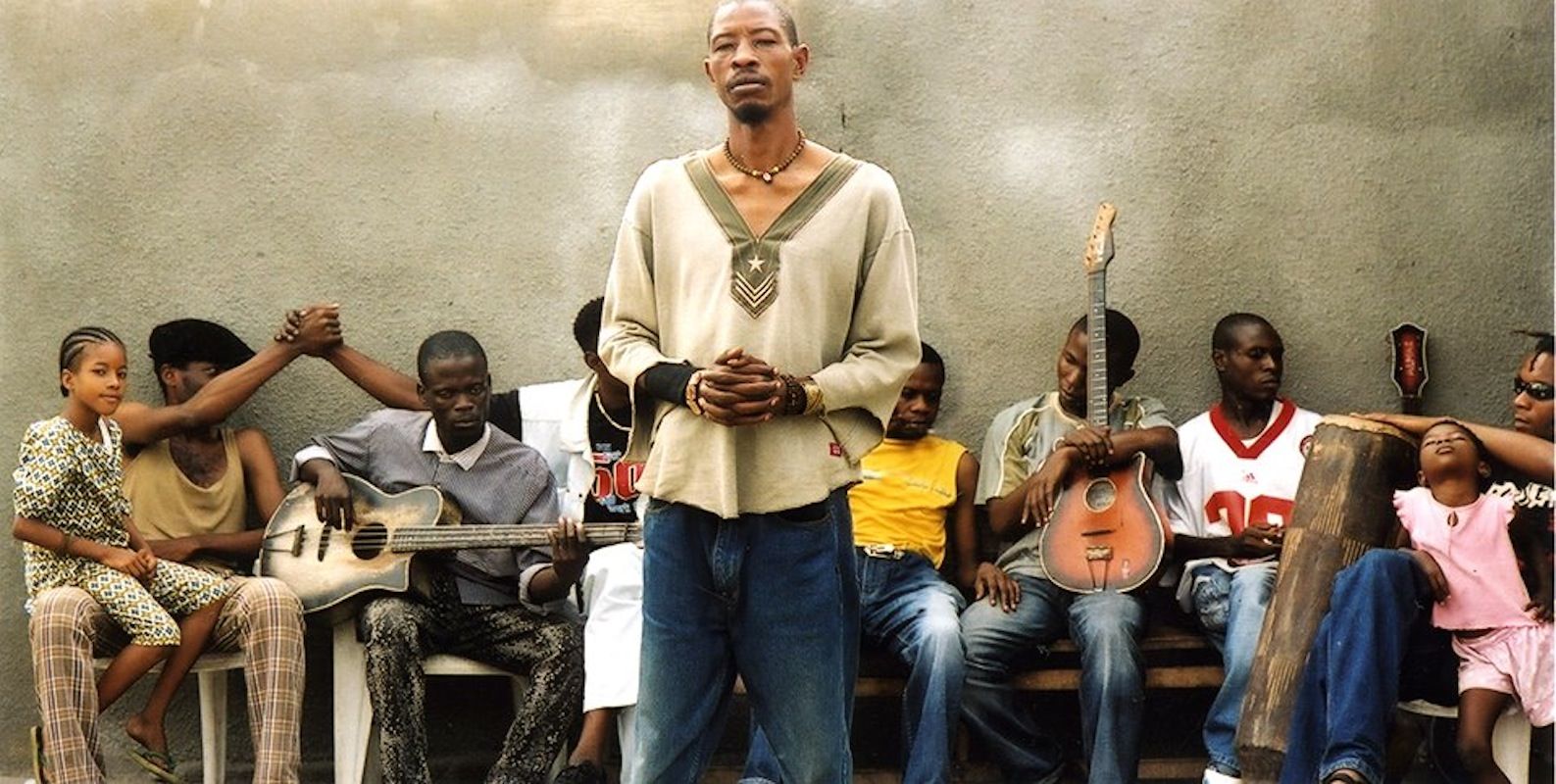

Jupiter & Okwess

ARTIST BIO:

Veteran stars of the Kinshasa street music scene Jupiter & Okwess return with their fourth album, Ekoya, their first for French label Airfono. This album represents an exciting new chapter for the band, blending their signature sound of soulful Congolese funk, rock and soukous with new influences from across Latin America, inspired by eye-opening cross-cultural encounters and the shared history of African people on both sides of the Atlantic.

Recorded not in Jupiter’s DR Congo, but rather in Mexico, Ekoya (‘It Will Come’) explores themes of change and resilience, of Indigenous peoples’ issues and the joys and struggles of everyday life. With guests including Brazilian singer Flavia Coelho, Mexican Zapotec rapper Mare Advertencia, and Congolese singer Soyi Nsele, and featuring lyrics in eight languages across its 12 tracks, Ekoya marks Jupiter & Okwess as both proudly Congolese and profoundly international.

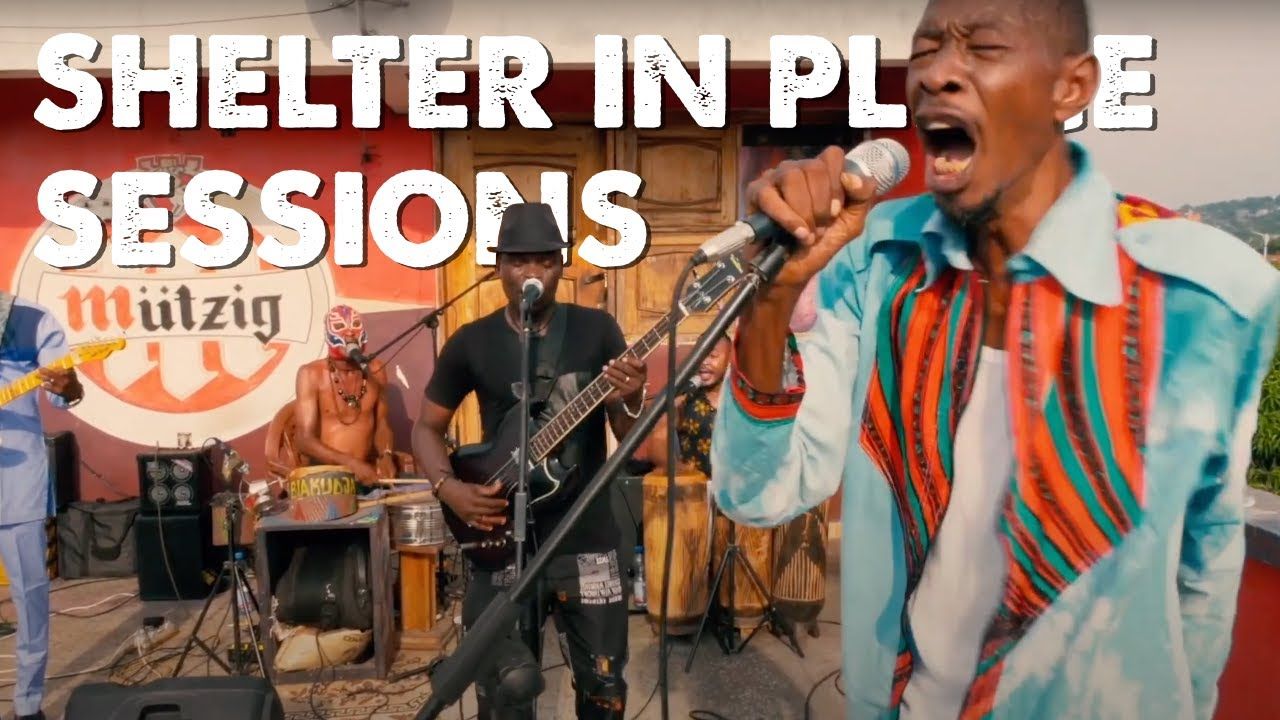

This is music that is unmistakable in its origins, its rhythms and melodies shaped by three decades of evolution on the streets of Kinshasa. But Latin America looms large over Ekoya. The album was conceived in 2020, when Jupiter & Okwess were touring South America, an adventure shaped by the spectre of lockdowns. Once the tour concluded, the band were forced to pause in Mexico before returning home – a transformative experience as they found themselves immersed in Latin American culture. Jupiter reflects: “Latin America has influenced us a lot... but our music hasn’t changed, it has just been given a new dimension. When we were there, we discovered things that pushed us to think differently. Because it’s like a continuation of Africa. There are people there who have African roots, Congolese roots – they are part of the story of Africa. They are part of us, and they are a part of our music.” When it came time to record the album, Mexico was the natural destination, where they spent time in studios in Guadalajara and Mexico City, and worked with producers including the renowned Camilo Lara (Pixar’s Coco; Marvel’s Black Panther: Wakanda Forever).

Since his debut in 2013, Jupiter’s sound has been defined by its weight, a purposeful heaviness, a rawness, even a darkness tinting the driving Kinshasa funk-rock and the softer, more introspective and sometimes ominous moments. Those signature styles remain, but are joined here by moments of lightness, sometimes ascending to a full-on dance party with soukous at the forefront – a well-known Congolese style that itself is infused with an indelible Latin influence, shown to full effect on the song Nkoyi Niama. Okwess’ choppy guitars, bouncing bass, glorious harmonies and pounding beats push that classic sound to the next level.

All throughout his music, Jupiter displays his mastery of the poetic word, communicating deep meanings through proverbs and parables. Lead single Les Bons Comptes warns against being in debt to friends. “Good accounts make good friends,” sings Jupiter in French, adding in the Mongo language: “a deadbeat is like a cuttlefish, they only take and never give.” Be a good friend, be honest and pay your bills. The message is also taken up by Brazilian songstress

Flavia Coelho, whose lusciously smooth and light voice works a beautiful counterpoint to Jupiter’s resonant, gravel-worn rumble.

Themes of change and resilience permeate Ekoya. “Everything is changing, on a global scale,” says Jupiter. “Changes in politics, changes in climate. You feel it in Europe, and we feel it even stronger in Kinshasa. But, on the other hand, tout passera – everything will pass. After life, nothing. You don’t have to be so focused on material things, on money, on property – tout

passera. That’s not optimist or pessimist – it’s just the truth.” Resilience is also found in lyrics presented by powerful Indigenous women activists, including singer Soyi Nsele who calls upon the ancestors to intercede against the unthinkable destruction of the Congolese rainforest in the opener Selele; and rapper Mare Advertencia of the Mexican Indigenous Zapotec people, who leads a hard-hitting demand for rights and justice for oppressed communities around the world on the song Orgullo: “We demand our right to exist / For the memory of those they took from us / For the justice we are still seeking!”

When Jupiter was young, he wanted to follow in the footsteps of his father, who was a diplomat. But, as he says, “Destiny is complicated. Life changed, and my life was making music on the streets in Kinshasa. But now we are performing all over the world, doing interviews, telling the world about the Congolese people – well, now I have the chance to be a diplomat. I did it differently.”

Developed in Kinshasa, blossomed in South America, born in Mexico and now released on the world, Ekoya continues Jupiter & Okwess’ important work as skilled wordsmiths highlighting universal issues, as champions of a world that is safe and welcoming for all, and as musical diplomats of their very own brand of forward-facing roots-focused Congo sound.